The number of kidnappings in South Africa has been increasing sharply over the past year. In the first six months of 2022 an average of 1 143 kidnappings a month were reported to the police, double the monthly average in 2021 (700).

The increase in kidnapping for ransom and extortion cases “suggests that it has become an established and lucrative criminal practice in South Africa”, said the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime (GI-TOC) in a Strategic Organised Crime Risk Assessment report for South Africa published in September 2022.

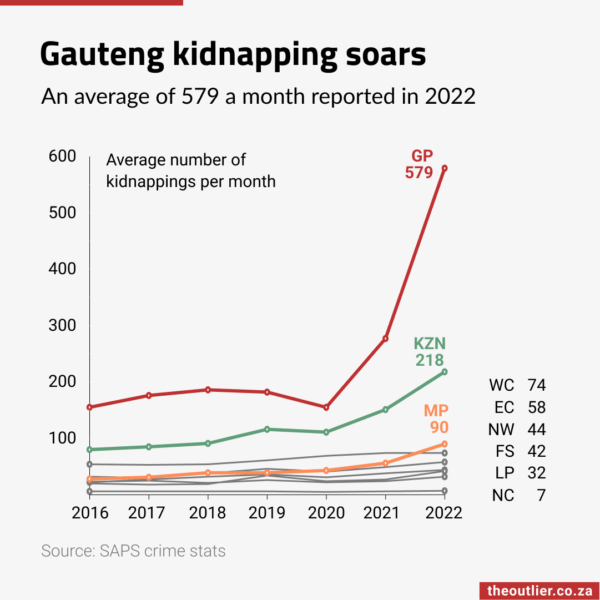

One province is driving this increase – Gauteng. The number of kidnappings reported in the first six months of 2022 are already 60% higher than the number reported for the whole of 2019.

Between January and June this year, an average of 579 kidnappings a month were reported in Gauteng, up from 277 in 2021 and 182 in 2019.

KwaZulu-Natal has the second highest number of kidnappings, with an average of 218 kidnappings a month for the first half of 2022.

Mpumalanga has shown the second-highest increase in kidnappings, after Gauteng. Cases in the first six months of 2022 (538) are already 15% higher than the total for 2019 (466). Mpumalanga police stations have reported an average of 90 kidnappings a month for 2022.

Police stations with the most kidnappings

This provincial pattern is reflected in the 20 police stations that reported the most kidnappings in the first six months of 2022; three are in KwaZulu-Natal (Inanda, Umlazi and Pinetown), one is in Mpumalanga (Delmas) and the rest are in Gauteng.

The two stations that reported the highest number of kidnappings between January and June this year are Vosloorus (114) and Kempton Park (101), both in Gauteng.

The precincts with the highest number of reported cases in Gauteng tend to be clustered.

Jhb Central, Jeppe, Booysens, Moffatview and Mondeor precincts are grouped in the centre of the city edging south.

Vosloorus and Heidelberg are very close to each other on the N3 highway to Durban in the south-east of Johannesburg.

Randfontein, Westonaria and Orange Farms are grouped together to the south west. Orange Farms, Evaton and Vanderbijlpark precincts are close to each other near the N1 freeway.

Further afield, there are two precincts in the top 20 to the north of Pretoria, Mabopane and Rietgat, and Delmas, to the east, which is in Mpumalanga province, on the border of Gauteng.

Not just rich targets

These precincts are not in the rich suburbs of Johannesburg and Pretoria. In fact, many of them are in low-income areas.

“Many cases we are looking at involve average earners with no visible source of disposable money,” said private investigator Kyle Condon, owner of D & K Management Consultants, which specialises in helping international and South African companies manage crime risk and fraud.

Wealthy people have the resources to increase their personal security. Lower-level earners are easier targets and they don’t draw as much media attention or dedicated police response, he said.

“There is a definite increase in lower-income cases, and equally in the poorest of poor areas,” said Condon. “These victims often scrape together the ‘smaller’ ransom amounts and, in many cases, don’t report the crime at all.”

Small-scale to mega syndicates

GI-TOC’s organised crime report noted that groups involved in kidnapping range from “small-scale syndicates targeting people in vulnerable communities, seeking quick money in relatively minor amounts, to professional ‘mega-syndicates’ carefully targeting high-net-worth individuals, sometimes holding victims for months at a time.”

Ransom kidnappings make up only 5% of South Africa’s kidnapping cases, according to the South African Police Service. Most kidnappings are because of robberies and hijackings.

For example, some victims are held for only a few hours so they can withdraw cash from an ATM to pay for their own release, said Lizette Lancaster, a senior researcher and project manager for the Institute of Security Studies – a non-profit focusing on training and research in crime prevention, criminal justice and conflict.

Or victims are held hostage until they have transferred money electronically via e-Wallet, said GI-TOC in its organised crime report.

Ransoms can be as low as R1 000. For example, when opportunistic gangs target people in informal settlements or peri-urban areas whose families are believed to have access to some money, they demand amounts that are “large for a person living in these environments, but not so large that they cannot pay”, said the report.

On the other end of the scale, transnational crime syndicates involved in kidnapping can demand ransoms of millions of rands. These kidnappings are well organised and victims are extensively profiled, said GI_TOC.

Recent high-level kidnappings, often of high-profile foreign businesspeople, may be connected to a criminal organisation from Mozambique, said the report.

Syndicates from Pakistan and Bangladesh also operate in South Africa and “tend to target nationals from their respective countries who are resident in South Africa”.

Local copycat groups are mimicking these syndicates, but targeting South African nationals, the report said.

The covid-19 lockdowns have brought some new players to the kidnapping game, according to the GI-TOC. Cash-in-transit gangs, for example, looking for other revenue streams, started to pursue kidnapping because it’s “comparatively low-risk given that small-scale kidnappings are seldom reported.”

culled from Mail & Guardian